What is the history of Folsom Ranch?

Folsom Ranch, as part of the Folsom Plan Area south of Highway 50, has indications of human presence that go back hundreds of years. Ancient Native Americans, ancestral to the Nisenan Maidu, once used the area for food gathering and passed through en route to or from the American and Cosumnes Rivers. Few indications remain today, due in part to the extensive gold rush-era mining that occurred later.

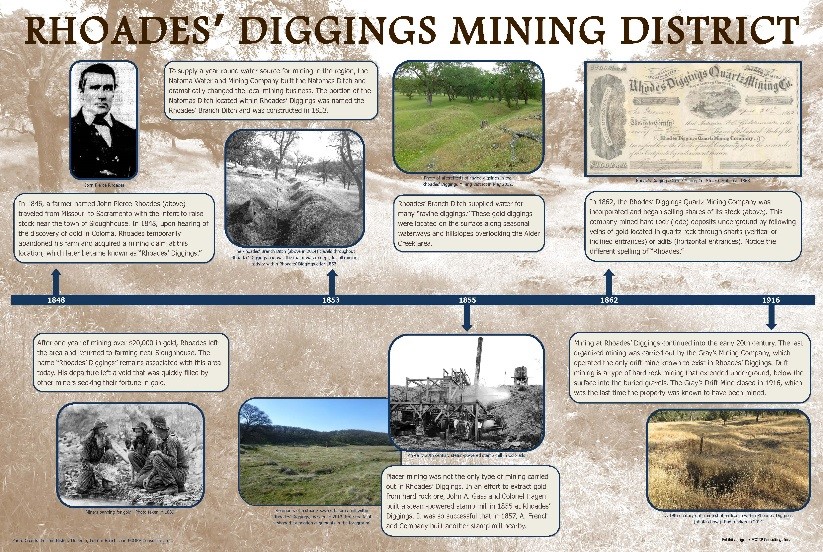

John Pierce Rhoades left the family farm along the Cosumnes River and moved north to the land south of Folsom in 1848 to acquire a mining claim.

According to historical accounts, mining was first carried out by John Pierce Rhoades, who began mining the land within and around Folsom Ranch at the beginning of the Gold Rush. Just months after the initial discovery of gold at Coloma and then along the South Fork American River in 1848, word spread quickly, sparking the beginning of what would be the Gold Rush. Soon thereafter, Rhoades established one of the earliest mining claims in the area.

Rhoades, a farmer from the Midwest, had traveled overland with his wife Matilda Fanning, six children, and other family members from Missouri to California in 1846. He settled that same year in the town of Sloughhouse with the rest of his family, including his father, Thomas, and brother, Daniel. In the autumn of 1847, Rhoades purchased Lot 5 of Jarred Sheldon’s ranch, known as Rancho Omochumnes, near the Cosumnes River in Sacramento County, with the intention of building a large farm and raising stock.

Upon hearing of the discovery of gold in Coloma, Rhoades temporarily abandoned the farm plot and moved north in 1848, where he acquired a mining claim and mined what would later be known as the Rhoades’ Diggings for nearly a year. According to one account, he, his father, and brother discovered gold in 1847—one year before it was discovered in Coloma; however, there is no evidence to suggest he was in the area earlier than 1848.

Although no historic documents have revealed the exact location of the original mining claim known as “Rhoades’ Diggings,” several historic maps identify “Rhoades Diggings” as being present in and around Folsom Ranch. This area could also have been named Rhoades’ Diggings due to the location of the concentrated region of the Rhoades’ Branch Ditch, which follows the slopes of several rolling hills overlooking Alder Creek and its tributaries.

There have been many versions of the Rhoades name (e.g., Rhodes, Rhoads), but according to Gudde (2009), a descendant of the Rhoades family, Bernie Rhoades, owns several legal documents signed by Thomas Rhoades, the father of J.P. Rhoades, confirming that the correct spelling is “Rhoades.”

Based on historical accounts, the Rhoades’ mining claim was very successful, with some reports suggesting that Rhoades and his family mined more than $20,000 in gold during the year they mined the area. For unknown reasons, Rhoades abandoned his mine claim in 1849 and moved back to his ranch to resume his plans for large-scale farming and stock raising. After his first wife died in 1851, he remarried a year later, and he and his new wife had another eight children (five survived), all boys. In 1863, Rhoades was elected a Republican member of the California State Assembly, 16th District, and remained in that position until 1865. He was also a school trustee for 20 years. Rhoades died in the winter of 1866 at 48 years old. He is buried in the Sloughhouse Pioneer Cemetery, and his original mining claim has been known as “Rhoades’ Diggings” ever since.

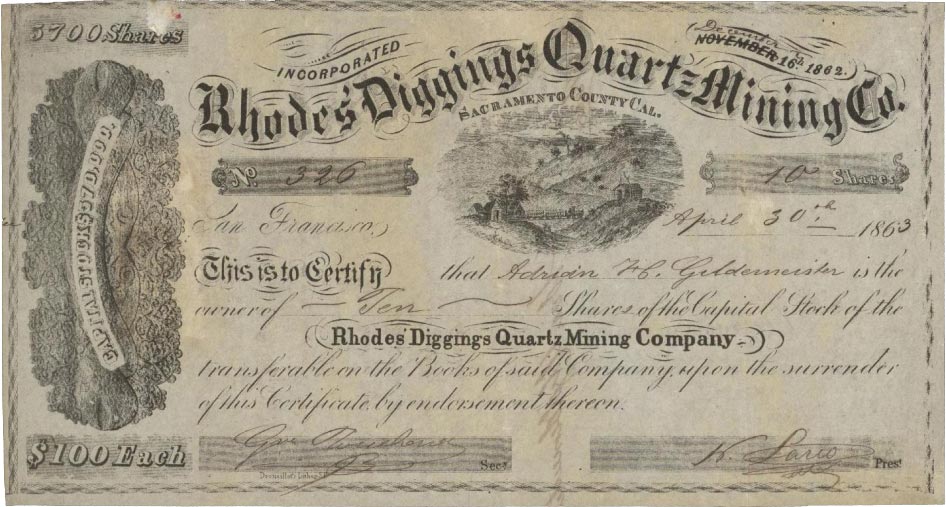

Archival evidence suggests that mining in the vicinity of Rhoades’ Diggings continued from when Rhoades left the diggings in 1849 and when the Rhoades’ Branch Ditch was constructed in 1853. By 1851, Rhoades’ Diggings had enough inhabitants that it was established as a voting precinct by Sacramento County for the 1851 general election. In addition, Emery Babcock, who was the owner of the “Babcock House” (located at Rhoades’ Diggings) was issued a three-month liquor license on December 8, 1851 through the Sacramento Court of Sessions.

Rhoades’ Diggings was fed by water from upper Alder Creek, which flows generally southeast to northwest through the Folsom Plan Area. As Alder Creek was seasonally dry in the summer and fall, mining prior to 1853 took place only during the winter and spring. Therefore, the area in which Rhoades’ Diggings is located was entirely dependent upon rain water prior to 1853, when the Natoma Water Company constructed the Natomas Ditch and Rhoades’ Branch Ditch. Although J. P. Rhoades had long since departed the area, the ditch retained the name of the diggings’ first miner.

With the decline of gold mining in the area came a shift toward ranching and homesteading. One of the more well-known figures was William Oliver Carpenter. Born in the town of Posey, Franklin County, Indiana in 1832, Carpenter grew up in farm country in a family of modest means. When he was 20 years old, he traveled to California. Upon reaching the state in 1852, Carpenter engaged in mining for gold in Sacramento County. However, in an effort to obtain regular employment, a good portion of his early days in California were spent teaming and freighting for the mines, and hauling goods and supplies to the miners. After a short time involved with the mining industry, he soon returned to the business of dairying and stock raising, and eventually became very successful.

Carpenter, who married Julie Long of Wales, had three children, George, Annie, and William Jr. In 1870 and 1880, the census listed Carpenter as a farmer which, along with the 1870 County Assessor’s map, shows him as the owner of 400 acres in what would become Carpenter Ranch, just south of the City of Folsom.

In 1877, Carpenter was involved in an altercation with a neighbor near his Folsom property that resulted in murder charges against him. According to historical newspaper accounts, Carpenter traveled to Joseph Gould’s house late one evening to retrieve cattle that Gould had corralled with his own, violating trespassing laws. Carpenter broke the corral in order to retrieve his cattle and returned to his residence. Later that night Carpenter returned with a small group of armed men to confront Gould. Gould’s son approached Carpenter’s group to discuss the situation, which soon escalated as the younger Gould shot Carpenter in the hand after Carpenter leveled his shotgun at him. Upon seeing Carpenter fall to the ground, his men fled the scene. The elder Gould exited his house and upon reaching the corral, was promptly shot in the chest by Carpenter, and died later from his wounds. Carpenter and his men were arrested on murder charges the evening of March 3, 1877. By December 1877, the case had been dismissed and Carpenter’s men had been absolved of the murder charges because Carpenter had been found innocent of the crime (Sacramento Daily Record 1877). According to County Assessor maps from 1870, Gould’s property was situated to the northeast, bordering Carpenter’s land.

In 1882, Carpenter owned 2,300 acres and by 1892, he was managing approximately 900 head of cattle on 3,000 acres of property located just south of Folsom at Carpenter Ranch. Additionally, he was said to have owned 740 acres in Emigrant Gap and another 1,700 acres near Truckee. This suggests that Carpenter was moving his cattle to higher elevations for grazing during the summer.

By 1906, Carpenter had passed away from a “hemorrhage of the lungs.” His wife Julie died two years earlier in 1904 of pneumonia. It is unknown what happened to his daughter, Annie. The census for 1880 listed her as 15 years old and living with her father and mother, but no other records for her were located. It is likely that she married and took the name of her husband. By 1911, according to the County Assessor’s map for that same year, the Carpenter family no longer owned acreage in the Folsom area.

Folsom Ranch was also the home to John E. Butler and his wife, Electa. Butler was born in Kilkhampton, Cornwall, England in 1827. He originally moved to Illinois as a child and then came to California to ranch sometime after the Gold Rush. He married Electa Louesa DeWolf in 1875 in San Jose and they both resided in the Folsom area, where they raised hogs, horses, cattle, sheep, and poultry. John Butler died in 1911, leaving his property to Electa.

Joseph and Lewis Tomlinson, brothers from West Virginia, were miners and then livestock farmers who lived in Folsom Ranch from the 1860s through the 1880s. The Tomlinson families continued to live on the property through the early 1900s. Joseph Tomlinson, or “Uncle Joe,” as he was called by his neighbors, was born in West Virginia on April 8, 1814 to Samuel and Lovisa (Purdy) Tomlinson. Joseph Tomlinson bought 160 acres on and around the Sacramento to Placerville Road (currently known as White Rock Road), in 1872. The property he purchased included the abandoned What Cheer House, which had been one of many inns built to house the Gold Rush-era miners and travelers along the road between Sacramento and Placerville. A bizarre incident occurred on the Tomlinson property in 1885. A tornado, described as a “funnel-shaped cyclone,” blew through the Tomlinson property and other ranchers’ and farmers’ land. The tornado leveled buildings, destroyed wagons, and killed livestock in its path. According to an article dated November 9, 1885 in The Sacramento Bee, Frank Tomlinson, described as the owner of a ranch in El Dorado County, mentioned that trees were uprooted and water was dispersed throughout his yard as a result of the tornado. The article states that two barns were blown down and several wagons were thrown and “smashed to atoms” nearby. Mrs. Tomlinson, presumed to be Alta, informed the newspaper that she saw the cyclone coming from several miles away and watched as her livestock fled. No individual was reported killed or injured from the cyclone, but it significantly damaged the area.

With the influx of gold miners, ranchers, and farmers to the area came the need for improved transportation networks. During the early use of the Placerville Road, both prior to the road improvements from 1851 to 1857 and after, several inns sprang up along the route for the new travelers. The aforementioned What Cheer House, White Rock Springs Ranch, and Brooks Hotel are examples.

The old White Rock Springs Ranch on what became the Wilkinson property at what is now a part of the Folsom Plan Area.

The Placerville Road was a primary contributor to the economic growth of the area around White Rock by means of the inns. In addition to the inns that developed, ranchers and farmers in the area were more able to deliver their products to the nearby busy towns of Placerville and Sacramento via the Placerville Road.

Later, in 1877, the Sacramento Valley Railroad Company and the Placerville & Sacramento Valley Railroad Company were merged to form the Sacramento & Placerville Railroad Company, which operated rail service from Sacramento through Folsom to Shingle Springs, with a continuation to Placerville over track owned by the Shingle Springs & Placerville Railroad Company. The tracks remain along Old Placerville Road to this day.

What is being done to preserve or document the history?

In compliance with the environmental review and permitting process under the California Environmental Quality Act, National Environmental Policy Act, Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, the history and archaeology of Folsom Ranch and the specific plan area has been studied and documented by professional historians and archaeologists over the past two decades. Much of the research to uncover, document, and preserve the history began in 2005 and continues now under the guidance and oversight of the US Army Corps of Engineers, California State Historic Preservation Officer, and City of Folsom. These efforts include detailed recording, photography, videography, laser mapping, archaeological excavations, and archival research, among other methods. Federal law requires that this work be carried out by professionals who meet the Secretary of the Interior’s Professional Qualifications Standards to ensure that the resources are not harmed in the process and that the documentation meets the permit requirements.

In addition, by law, 30 percent of the specific plan area must be preserved as open space. Because these open space areas coincide with many cultural resources, a representative cross section of resources will be preserved in perpetuity and managed appropriately.

A number of interpretive panels have been designed and will be installed along the miles of public walking paths and trails within Folsom Ranch and the surrounding land in the Folsom Plan Area.

Where can I find more information about the history of Folsom Ranch?

A number of interpretive panels have been designed and will be installed along the miles of public walking paths and trails within Folsom Ranch and the surrounding land in the Folsom Plan Area. Once installed, these panels will tell the story of the people who once lived in this area, including ancestral Nisenan Maidu, gold mining, and historic inns. These panels, as well as volumes of historical syntheses and documents, were prepared as conditions of federal and state permits required for the project.

The main mining ditches were documented through the Historic American Engineering Record program, administered by the National Park Service, and reports generated are on file with the Library of Congress in Washington DC.

There are also many other sources of information on historic mining in the area, including:

Askin, D. and R. Docken, 1980. The Natoma Station Ground Sluices: An Historical Study. Prepared for the Natomas Company.

Caltrans, 2008. Historical Context and Archaeological Research Design for Mining Properties in California. Division of Environmental Analysis, California Department of Transportation, Sacramento. http://www.dot.ca.gov/ser/guidance.htm#mining_study.

Clark, William B., 1970. Gold Districts of California. California Division of Mines and Geology, Bulletin 193. San Francisco.

Cross, Ralph H., 1954. The Early Inns of California. Cross & Brandt, San Francisco, CA.

Davies, J., 1999. Rhoades Diggings. Manuscript on file, Rhoads’ Diggings Binder, Folsom History Museum, Folsom.

Folsom Historical Society, 2014. History of Folsom, Mining Towns, and the Natoma Company. On file at the Folsom History Museum, Folsom, California.

Gudde, Erwin G., 1975. California Gold Camps: A Geographical and Historical Dictionary of Camps, Towns, and Localities Where Gold Was Found and Mined; Wayside Stations and Trading Centers. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California.

Wilson, N. L., and A. H. Towne, 1978. Nisenan. In Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 8: California, edited by R.F. Heizer, pp. 387-397. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

How can I get involved in archaeology and historic preservation?

Because of the permit conditions and professional qualification requirements, all cultural, historical, and archaeological research must be done by people who meet the Secretary of the Interior’s Professional Qualifications Standards. Therefore, there are no current opportunities for the public to be involved in the project; however, after the project is completed, any opportunities for volunteering through the Folsom Historical Society or as site stewards with the City of Folsom will be posted as they arise. In the meantime, the US Forest Service provides opportunities for non-professionals to gain experience in archaeology and site documentation through the Passport in Time program. More information can be found at www.passportintime.com.

Why are archaeological sites kept confidential and can I collect artifacts?

Archaeological and Native American site locations are protected from public distribution by state and federal law because of the threat of damage or destruction, either knowingly or unknowingly, by the public. Collection of artifacts is prohibited by the public. Specifically:

- Sections 6253, 6254, and 6254.10 of the California Code authorize state agencies to exclude archaeological site information from public disclosure under the Public Records Act. Specifically, Section 6254(r) exempts from disclosure public records of Native American graves, cemeteries, and sacred places maintained by the Native American Heritage Commission.

- Because the disclosure of cultural resources location information is prohibited by Section 9a of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (16 USC 470hh) and Section 304 of the NHPA, it is also exempted from disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act (Exemption 3; 5 USC 5).

- Sections 5097.993-5097.994 establish as a misdemeanor, punishable by up to a $10,000 fine or both fine and imprisonment, the unlawful and malicious excavation, removal or destruction of Native American archeological or historic sites on public lands or on private lands. Exempts certain legal acts by landowners. Limits a civil penalty to $50,000 per violation.

- Section 622 of the California Penal Code establishes as a misdemeanor the willful injury, disfiguration, defacement, or destruction of any object or thing of archeological or historical interest or value, whether situated on private or public lands.

For this reason, the locations of archaeological sites in Folsom Ranch and the plan area cannot be disclosed to the public. Uncontrolled or unescorted visitation by the public is also prohibited. In addition, the entire specific plan is under private ownership, and trespass laws are being enforced.

What happens to the archaeological materials and artifacts that are found?

As a condition of federal permits, culturally significant artifacts have been permanently curated at the David A. Fredrickson Archaeological Collections Facility at Sonoma State University, where they will be preserved in perpetuity and available for research by qualified professionals who meet the Secretary of the Interior’s Professional Qualifications Standards. Artifacts not selected for curation have been offered to the Folsom Historical Society for incorporation into their collections and for public review.

In the event that archaeological materials are encountered during project construction, state and federal law require that construction activities at that location halt so that a qualified professional archaeologist, in coordination with the US Army Corps of Engineers, California State Historic Preservation Officer, City of Folsom, and Native American tribes (if applicable) can consult on an appropriate course of action. This includes evaluation of significance and treatment in accordance with state and federal laws. Significant artifacts recovered will be treated as described above.